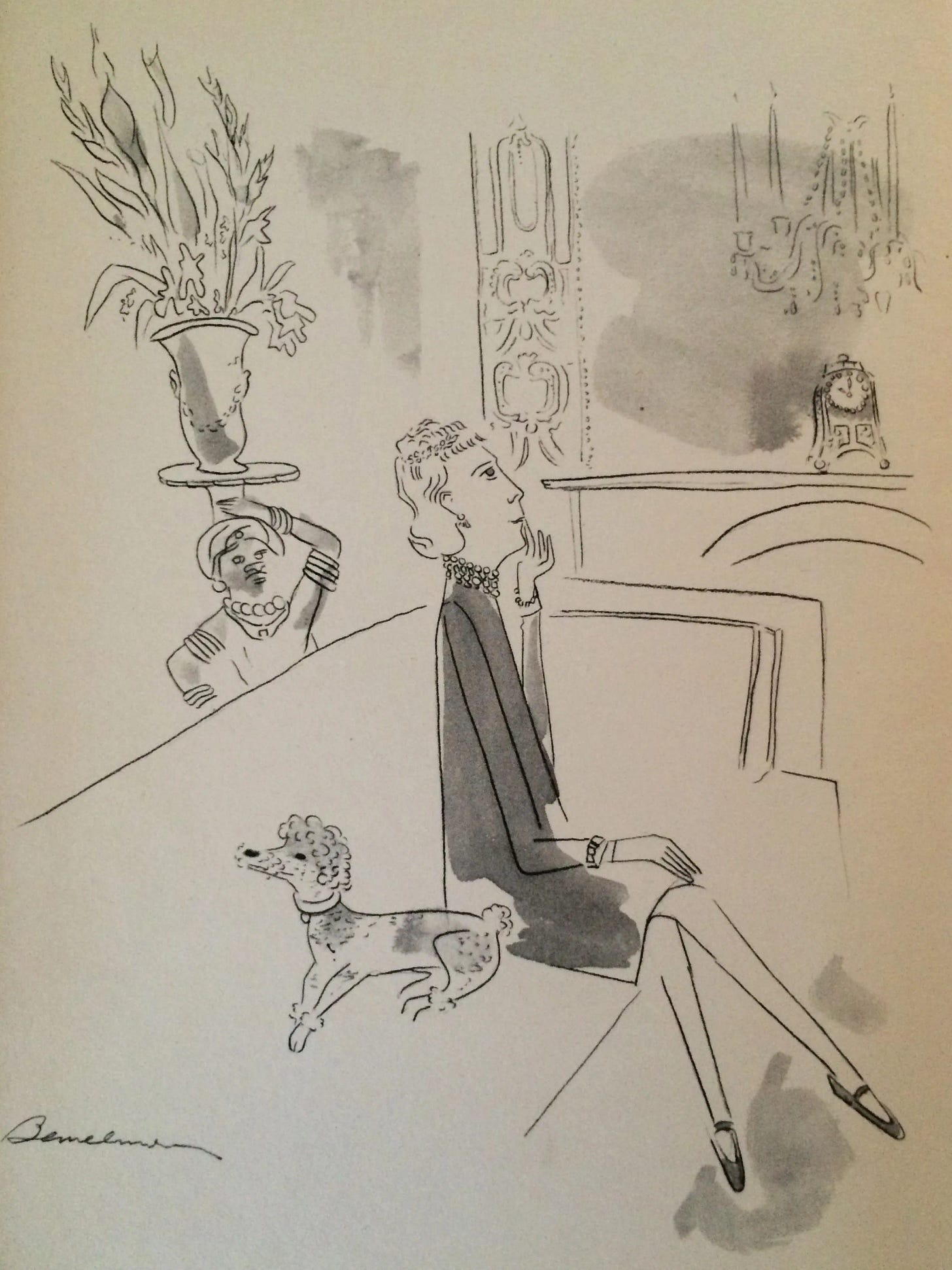

“A tiny woman who liked to wear short white gloves and to carry at least one little dog, she furnished homes from Manhattan to Paris, Saint-Tropez to Beverly Hills.”

I recently came across the eccentric worldly life of Elsie de Wolfe! Born in New York in 1865, Elsie is credited for inventing the interior design profession. She believed good taste to be accessible to all, as opposed to being based on wealth and material goods. “What she had discovered was not a new style but a new sense of the way a house should function,” de Wolfe’s biographer Jane S. Smith wrote. It was “a synthesis of comfort, practicality, and tradition that would turn out to be precisely what the coming century would crave.”

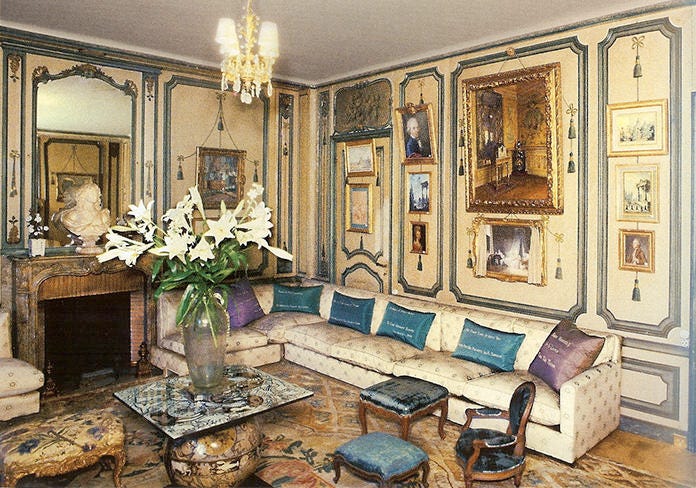

She was infatuated with Europe, a francophile to be exact. She destested the Victorian style of her time, and was passionate about the 18th century, which had fallen out of fashion. She incorporated popular 18th century colors in her decor, such as eau de nil, vert saule, and jaune poussin, deflecting it all with accents of brighter hues, and animal prints! Her interiors have been described as “innovative and anti-victorian”, she had a “less is more” approach which was revolutionary! Notably, in a period when consummtion reached new heights, Elsie redefined taste as an accessible virtue. She thought that good taste for everyone, just like anyone could learn good manners. In her words, “I believe in plenty of optimism and white paint, comfortable chairs with lights beside them, open fires on the hearth and flowers wherever they ‘belong,’ mirrors and sunshine in all rooms.”

Still, she was no innovator, rather she looked to the past and accommodated older pieces in terms of their stability and utility, placing them in contexts that made them feel fresh and relevant. She rejected modernism, in favor of accepting “the standards of other times, and adapt them to our uses.”

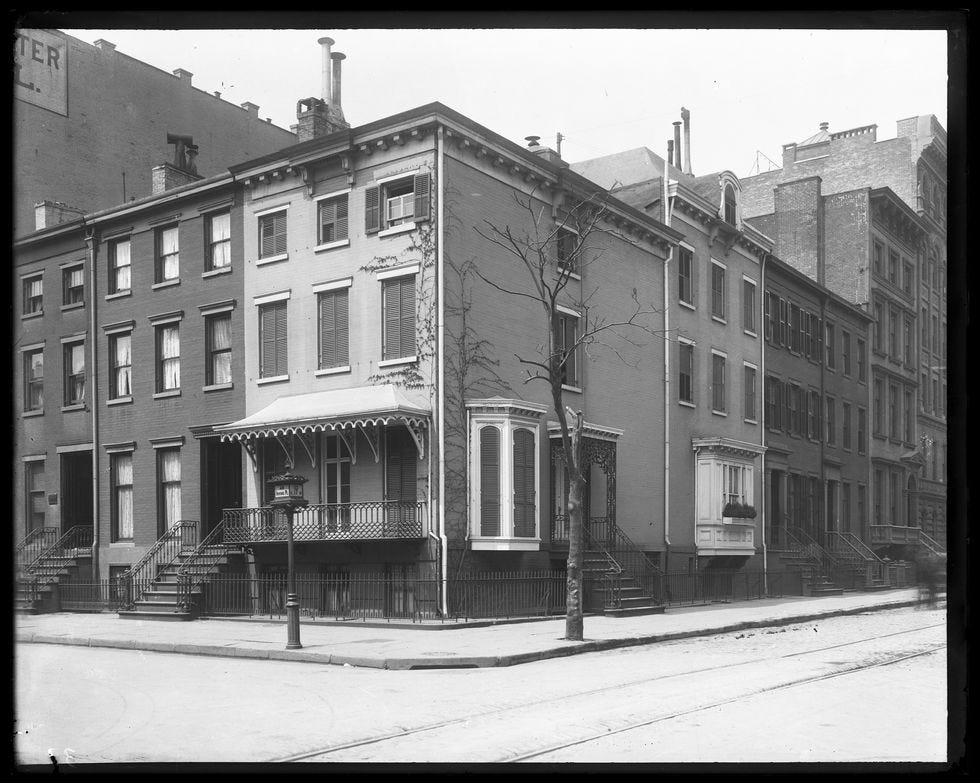

Elsie was raised in New York, but she was sent to Scotland for school at the age of 10. She described herself as an ugly child, and in adulthood would become an early adopter of yoga, plastic surgery, and fad diets as detailed by this 1938 New Yorker profile of her. Her father was a doctor, although the family had debt and moved homes multiple times during her childhood. They lived in brownstones, which Elsie thought were “hideous and dark.”

She was presented at Court to Queen Victoria in 1883 at the age of 18, she wandered London society until returning to New York at the age of 20. In New York she made friends with Anne Morgan (daughter of JP), Anne Vanderbuilt and Sarah Cooper Hewitt; her broader circle included Ludwig Bemelmans (of Madeline fame), Robert de Montesquiou, George Cukor, or Katharine Hepburn. Elsie began doing theater, which was a popular form of charity fund-raising back then. It is only when her father passed away that she began doing theater professionally. Going professional was facilitated by Elisabeth Marbury who was a theater agent representing Oscar Wilde, Cole Porter, George Bernard Shaw and many more. Elsie toured for two years, and then formed her own theater company in 1901, retiring from the stage in 1905 when she was faced with the success of her understudy. Apparently, Elsie never received a single good review throughout her four years on stage. Instead, Elizabeth Marbury and Sarah Cooper Hewitt encouraged Elsie to start decorating homes, because of her natural styling abilities, which was made clear when Elsie became more known for her fashion than her acting. Elsie was fashion obsessed; she apparently wore kinky Mainbocher dresses, and actresses always copied her theater costumes.

It was the Hewitt sisters who introduced Elsie and Elisabeth, and the two became partners for over forty years. In 1892, Elsie and Elisabeth together moved into Washington Irving House, which would give its name to Irving Place in New York. Elsie took on the redecoration of this house as a challenge. The house was a dark house and Elsie was unhappy with many aspects of it. The redecoration process features heavily is her book, In Good Taste, which is largely a colloquially written mix of practical advice and personal experience, as well as collections of articles Elsie wrote for magazines such as House and Garden or Good Housekeeping. With proclamations along the lines of “the man makes the house, the woman makes the home!” the book reads a bit outdated, and most of the key ideas may be taken for granted, because her revolutionary thesis around comfort and functionality in the home, is a given these days. So you can skip the book, but stay for the memoir!

Elsie’s first job would be to decorate the Colony Club, the first private social club for women. And so, she began to grow her international client list! The highlight of her career would be the mansion that Henry Clay Frick was building at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Seventieth Street. Elsie advised Frick on purchases, guiding him through Sir Richard Wallace’s collection for Frick’s future museum. Elsie’s ten per cent commission made her income one of America’s highest that year! Other notable clients included Amy Vanderbilt, Condé Nast, Cole Porter and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. In her autobiography, "After All," she called herself a "rebel in an ugly world," saying, "I opened the doors and windows of America, and let in the air and sunshine."

Elsie lived in France throughout WWI and in between the wars. She and Elisabeth owned a mansion in Versailles, and Elsie became famous for hosting parties in Paris with “skimpy” menus, decadent flower arrangements, hosting a mix of intellectuals and socialites, from Coco Chanel to Gertrude Stein, or Wallis Simpson. In 1926, at the age of 60, Elsie surprised everyone when she married Sir Charles Mendl, a British diplomat, after openly living with Elisabeth as a lesbian for decades. “According to Hilda West, de Wolfe’s longtime housekeeper, de Wolfe had simply decided she wanted a title (after the marriage, she was known as Lady Mendl). Whatever the explanation, the marriage appears to have been primarily for social convenience: the couple entertained together, but they kept separate homes.”

The New Yorker notes that Elsie’s decor sensibilities did not extend to art. Apparently, “a lifetime of choosing paintings based on whether they matched the sofa left her unable to develop any deep appreciation of art.” Her reaction to the Parthenon was, “It’s beige! My color!” and when visiting Gertrude Stein, she was horrified at the sight of a Dalì work. She also lacked sensibility when it came to politics: one of her great parties in the summer of 1939 made its way in the politics section of the New York Times for being the setting for a meeting between the French foreign minister, Georges Bonnet, and the German ambassador to Paris, “who had been discussing the status of Danzig just a few hours before.” As written by Ruth Franklin, “A person’s house may well mirror his or her character, and de Wolfe’s was too crowded with bedazzlements for her to notice the world-changing drama taking place literally in her own back yard.”

When WWII broke out, she and Sir Charles Mendl left Paris for California. They were pressed for cash, as their foreign assets were frozen, though they a few American investments. That is how Elsie found herself decorating movie sets for 20th Century Fox. Although, she apparently also had a couple of screen tests at Warner Bros. According to gossip columnist, Louella Parsons, it was not in hopes of landing a leading film role, but rather “so she could see herself as others see her.” Elsie also attempted hosting a radio show broadcasted from the Beverly Hills Hotel, entitled Breakfast at the Beverly Hills – it flopped after the first episode.

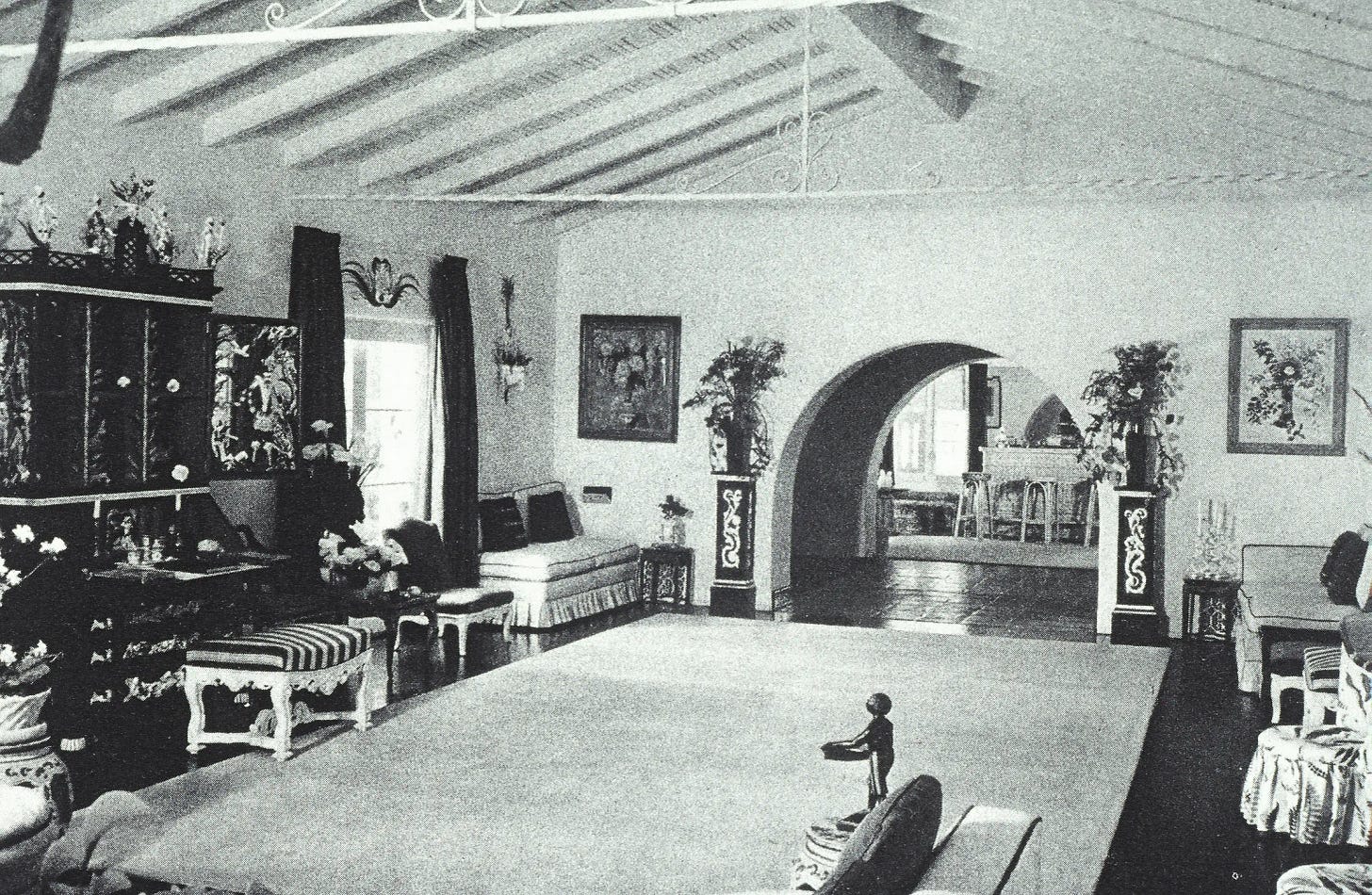

Elsie and Charles stayed with friends upon arriving in L.A., and in 1942 bought a 1920s Beverly Hills hacienda, naming it After all, the same name as Elsie autobiography. Hollywood, she exclaimed, was “the new focal point of civilization.”

About her home and time in L.A., Architectural Digest writes,

Following months of expert massaging, the 3,500-square-foot dwelling came to embody the kind of youthful vitality that Elsie strove to maintain in herself through plastic surgeries, hormone treatments, headstands, and fad diets. White paint refreshed the flowerpot-red house inside and out, and green-and-white-striped canvas curtained the front door and arched loggias, the latter wittily nicknamed the Rue de Rivoli. Grapevines twirled through the Inquisition-style iron window grilles. Begonias and daisies, all white, frothed in the garden, where towering topiaries stood like sentinels and variegated ivy flourished. The swimming pool was filled in to make room for a mature olive tree, though the first specimen arrived far too small for Lady Mendl’s liking.

Frank Sinatra dropped in and left duly dazzled. Greta Garbo and the stripper Gypsy Rose Lee met there for the first time in an unlikely face-to-face engineered by Lady Mendl, a mutual friend. Salvador Dalí sketched a horse in the guest book. Actress Hedy Lamarr was a regular, so much so that the Mendls served as matron of honor and best man at one of her weddings. Afternoons might be spent playing gin rummy with the likes of director George Cukor and radio magnate Atwater Kent or dropping by movie sets. After dark, Lady Mendl would wrap herself in a knee-length chinchilla coat (reputedly one of only two in Hollywood) and swan out to chic boîtes such as Chasen’s and the Mocambo. And when she wasn’t hitting the town with an energy that belied her years—in 1947, the 88-year-old signed 600 copies of her cookbook in a single go—she was masterminding unforgettable luncheons and dinners.

After the war, Elsie returned to her house in Versailles, Villa Trianon, where she died in 1950. To this day, she is still celebrated for the vitality she brought to the home, and turning the page of Victorian gloom. She is remembered for the aura of celebrity she brought to the profession, she is after all, the reason for the celebrity interior designer today! Reading about her, I was mostly amused by her eccentricity and fascinated by the personalities she crossed paths with.

Until next time!

Franny